You know that old story of the “overnight success?” A band you’ve never heard of bursts onto the scene and takes the world by storm. Often you find that they have twenty years of hard work and paying their dues before finally achieving their goal. The same is true of Hattie McDaniel.

Born to former slaves, and growing up in the abject poverty that followed America’s black population in the Jim Crow years, Hattie McDaniel was determined that a life of servitude and struggle was not to be her fate.

Her very first paid work was as a street performer at a carnival; from there she moved to stage plays, vaudeville, her own theater company, always reaching for the next challenge.

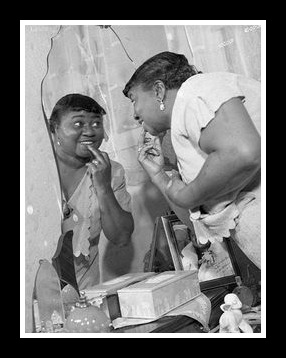

She was the first black woman to sing with an orchestra on the new medium of radio. She had a second career as a famed blues singer in the artistic hubs of Kansas City and Chicago. And a third as a songwriter. And a fourth as a recording artist. She was known as a saucy and clever comedian; famous in performer circles for her fire and her wit.

All through her artistic struggle, she was compelled to work as a domestic servant to keep food on the table and a roof over her head. How odd to be called a “red hot mama” and “an inspiration” by night and to put on a maid’s uniform and be anonymous by day.

She landed a plum job with Mr. Ziegfield and thought her troubles were over – until she was laid off and abandoned in a strange city. Hattie became a restroom attendant in a white nightclub, and lived the sitcom dream when the band was left without a singer. Hattie emerged from the powder room and blew everyone away. Little did they know they had a superstar in their midst!

It was time to take the plunge and move to Hollywood, where she registered with both a service laundry company (because she’s a practical person) AND Central Casting (because a girl’s got to have a dream!) She fit a desirable “type”, and soon was pulling in $7.50 a day as an extra in hundreds of movies.

Her brother Sam was a performer on “the Optimistic Donuts” radio variety show and got his sister an audition, and soon she was a regular known as “Hi-Hat-Hattie” – what’s more, the station soon gave her her OWN radio show, “Hi-Hat-Hattie And Her Boys” in which her saucy comedy took center stage.

Roles as an extra turned to speaking roles and soon to plum jobs earning $250 or more a week. She spent much of her money supporting black-owned businesses, assisting the less fortunate, and helping her family and friends to succeed. Her big break in Hollywood was as a back-talking maid in “Blonde Venus” with Marlene Dietrich (1932). And soon she was in high demand.

However, controversy surrounded Hattie McDaniel even from this early time; African Americans (particularly as represented by the NAACP) were tired of the old minstrel-show sterotypes perpetuated by the studios, and were criticizing the black performers who took these roles. (Though there were no better ones on offer, and the targets may have better been painted on the studios themselves.)

When Gone With the Wind began filming, Hattie McDaniel won the coveted role of Mammy due in no small part to her friendship with Clark Gable, who had already been cast as Rhett.

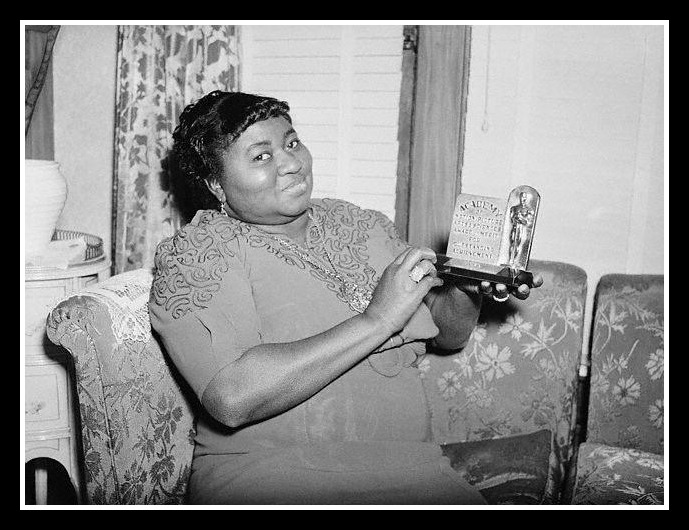

Hattie McDaniel, and the other black cast members, were not allowed to attend the premiere in Atlanta, nor were their photos to appear alongside those of the white members of the cast, so it was a victory of sorts that Hattie McDaniel made history later that year when she received the very first Academy Award ever given to a person of color. Even so, her table was a separate one in the back of the room.

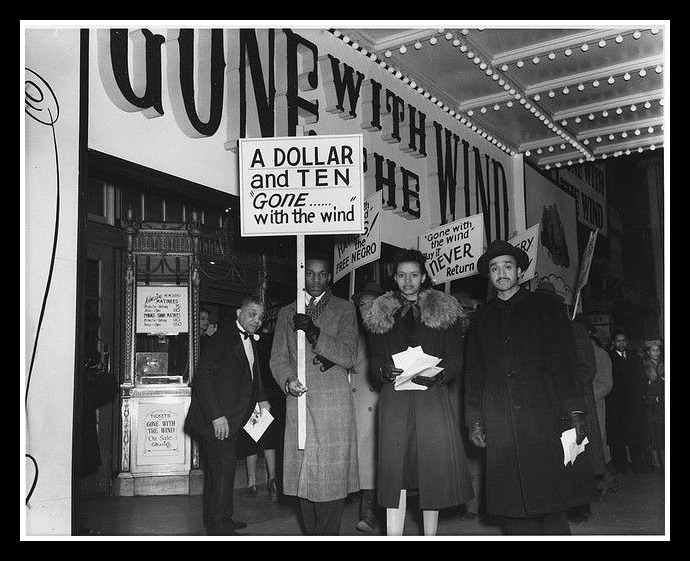

White audiences adored Hattie’s portrayal of Mammy, but it enraged many in the black population.

Protesters outside of a showing of “Gone With The Wind.”

Many black citizens resented the movie’s portrayals of old minstrel stereotypes.

She received letters calling her a “disgrace” from black servicemen engaged in WW2; rather than lashing out, she responded by heading the Hollywood Victory Committee, in charge of USO shows and morale building. McDaniel created a philanthropic society named les Femmes D’Aujourd’hui (The Women of Today), and joined Sigma Gamma Rho, a black sorority dedicated both to philanthropy and the advancement of equality.

After some white neighbors tried to remove her (and other black performers) from their neighborhood, McDaniel was instrumental in a groundbreaking and nationwide legal case to prevent “restrictive covenants”; agreements in residential developments that would prevent persons of color from buying into certain neighborhoods. They were ruled illegal under the 14th Amendment.

Though her movie career faltered after her appearance in Gone With The Wind, Hattie McDaniel found yet another career (is this #6?) as the beloved star of the radio sitcom “Beulah”. Ten million people tuned in for every episode! Harsh criticism of this role from the NAACP brought the simple rejoinder “I’d rather make $700/week playing a maid than $7 being one!” She believed that she represented a part of her former life with this role, a job that so many women of color were performing all over the country.

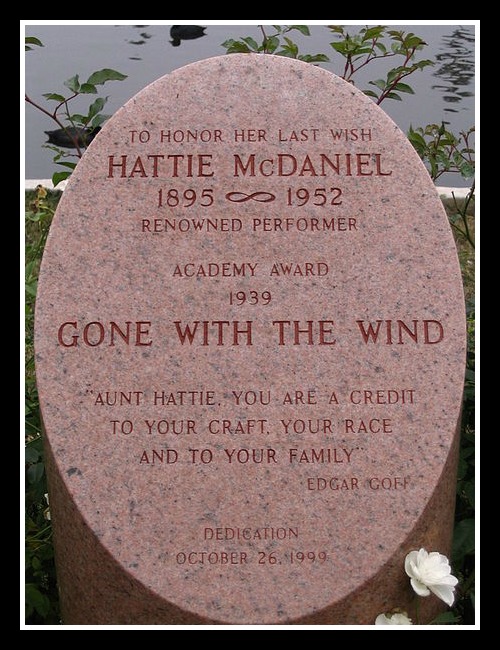

Health issues laid her low for the last year of her life; a heart attack followed by a diagnosis of advanced breast cancer led to her death on October 26, 1952.

Five thousand mourners attended her funeral. Refused burial in the “white” cemetery that was her first choice, she was laid to rest instead in the Rosedale Cemetery “Where the young of our race will be inspired by her for whom she did so much.”

Her final wish was honored, years later, with this memorial stone in what is now called the “Hollywood Forever” Cemetery.

A notable and touching homage to McDaniel’s legacy came in 2010; when accepting her Academy Award for her role in “Precious”, actress “Mo’nique dressed in a blue gown and gardenias, (the outfit that McDaniel had worn to her own ceremony in 1939,) and said “I’d like to thank Hattie McDaniel for enduring all that she had to, so that I would not have to.”

Hattie McDaniel was brave. She believed in the power of helping others, she persevered against great odds, immense setbacks, and criticism from all sides. She believed in herself, and she believed in a better future for all.

If that’s not a role model, we don’t know what is.

Music provided courtesy of musicalley.com

Closing song : “Take the High Road” by Sharon Robinson