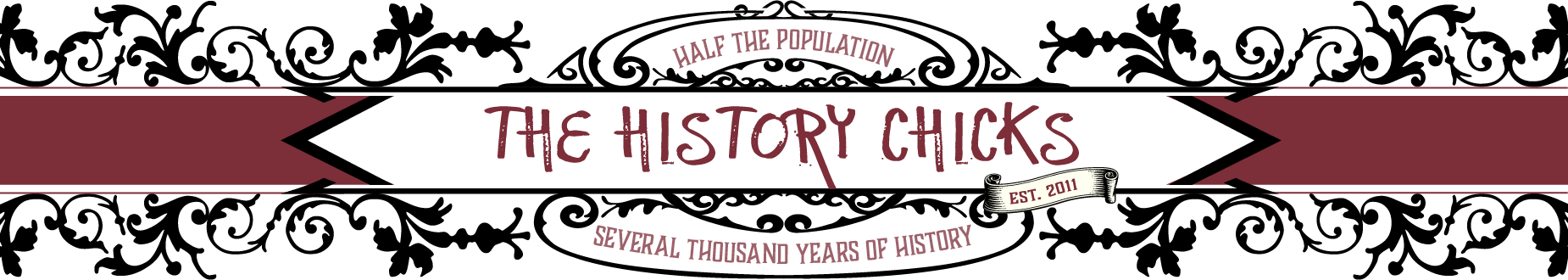

1. The Lansdowne Portrait

This is the famous painting that Dolley Madison helped to save from the British during their invasion of Washington, DC in 1814!

Senator William Bingham (perhaps the wealthiest man in the country) commissioned this iconic painting from the portraitist Gilbert Stuart in 1796. It depicts George Washington at the end of his two terms as president, as he prepares to cede power to his successor. Though not written into law, George Washington’s voluntary two-term limit became a custom that held until the election of Franklin Roosevelt for a thrid term in 1940!

The portrait was given as a gift to The Marquess of Lansdowne (known during this period as William Petty, the Earl of Shelburne) to thank him for his support of the American cause within the British Parliament.

The Earl (mostly against party lines, and in his own self-interest) worked tirelessly to promote the free trade between the United States and Britain, putting forth legislation that would treat the United States like any other sovereign country.

Senator Bingham, who had amassed his huge fortune largely by privateering and legitimate trade, benefited greatly from this advocacy. A long-distance friendship of sorts had sprung up from all of their correspondence about trade issues. Shelburne rose high in the British government, becoming the Prime Minister for the last months of the American Revolution.

I’m not sure I would love for someone to give me an unsolicted gift the size of an area rug, but I can certainly appreciate the sentiment behind it. This painting stayed in Europe until 1965, when it was sent on anonymous loan to the Smithsonian.

Stuart was paid a thousand dollars for his work on this painting. In 2001, the Reynolds Foundation bought it for $30 million dollars as a gift to the nation. It now resides in the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian, with copies in the White House, the US House of Representatives, and several other government buildings throughout the nation.

For a discussion on the symbolism in this portrait, please visit the interactive page at the Smithsonian Portrait Gallery at http://www.georgewashington.si.edu/portrait/index.html

*********************************

2. The Epergne

Dolley Madison was not only famous for her “squeezers” – her popular, well-attended balls in which everyone got about 10 inches of floor space. She also gave lavish dinners, which were carefully balanced between the refined elegance of a European court and the abundant offerings of the New World.

One element that was sure to be at the center of every fashionable dining table of the time was a silver epergne (Pronounced ay-PERN).

The top bowl was often filled with decorative fruits (and in later times, flowers), and the lower vessels held candied fruit, nuts, or small confections. The piece, loaded with tempting goodies, stood intact as a decorative centerpiece through all of the courses of a formal dinner, then guests helped themselves from it during the dessert course. (If there had been a tablecloth during the meal, the epergne was removed with the cloth, then replaced on the bare table for the dessert course.)

What are the origins of the epergne? During the 1600s, one would find a surtout in the middle of the table – simply a large tray which held and displayed the expensive spices and condiments to accompany a meal. The assorted height and materials of the containers lent a decorative element. The fruitier, a tiered display stand introduced later, more closely resembled the epergne. The fruitier would take the place of the surtout towards the end of each meal.

The epergne came into being around 1735, and most early examples were produced in the Rococo style, which used curved “shell” motifs. (think Marie Antoinette’s bedroom, for one example.) The mid-17th century fascination for Chinoiserie led to the inclusion of pagoda-like shapes and bells. (The example shown below is less than a mile from my house right now!)

By the time Dolley Madison was hosting her dinner parties, the epergne was a standard element of the well-appointed table…

The very latest fashion at the time Dolley Madison was holding court in the White House. This piece, circa 1810.

Though not everyone was enchanted with them. They were hard to see around, for one thing. The larger and more obtrusive they were, the less you could speak to the people in your party. From the book Foul Play, by Charles Reade (1869!)

“But their tongues were tied for the present; in the first place, there stood in the middle of the table an epergne, the size of a Putney laurel-tree;

neither Wardlaw could well see the other, without craning out his neck like a rifleman from behind his tree… “

- Once this was loaded up, good luck seeing the other side of the table! Circa 1771, candelabra added approx. 1838.

And does anyone remember the great lump in the middle of the table in Dickens’ “Great Expectations”?

“An epergne or centrepiece of some kind was in the middle of this cloth; it was so heavily overhung with cobwebs that its form was quite undistinguishable; and, as I looked along the yellow expanse out of which I remember its seeming to grow, like a black fungus, I saw speckled-legged spiders with blotchy bodies running home to it, and running out from it, as if some circumstances of the greatest public importance had just transpired in the spider community.”

- Of course, it was not an epergne at all, but her wedding cake, left to moulder for years and years. Yummy!

Modern-day historical romance writer Catherine Coulter refers to an “Ugly Epergne” in three of her books: The Nightingale Legacy (1995), The Wild Baron (1997) and The Countess (1999).

And the oddest Epergne story of all: Writer Dante Rossetti has a series of pet wombats, one of whom would commonly (and famously) sleep in the epergne during dinner parties!

” On grand occasions when a number of guests were invited to dinner, Dante Gabriel was in the habit of using the so-called drawing room on the first floor as a dining room. It was a large room with a good view out over the river. On the table in the centre of the room was a large epergne. Into this receptacle Dante Gabriel used apparently to place the somnolent wombat and there it would normally remain fast asleep until lifted down after the guests had gone. James Mc Neill Whistler told a particularly good story about one of these dinners. Among the guests were Meredith, who was talking brilliantly, and Swinburne, who was reading aloud from Leaves of Grass. The wombat was in the epergne and conversation flowed freely. However, the target of Meredith’s wit that night was Rossetti. As some of his patrons were present, Rossetti became embarrassed and eventually very cross. ‘The evening ended less amiably than it had begun, and no one thought of the wombat until a late hour, and then it had disappeared.’ A great search was instituted, but to no avail. Months passed until one day Rossetti sought his cigars for a guest. ‘Not a cigar was left but there was the skeleton of the wombat.”

At the turn of the present century, (and out of our period) the epergne turned from the display of food towards the arrangement of flowers. Trumpets of colored glass on tiered stands became the norm. Let me leave you with a picture of one of my favorites: