4. The sons and daughters of Mad King George

You would think, with so many children, that King George and his wife Charlotte would have ensured the succession. Au contraire. At the time of Princess Charlotte’s death in 1819, the marital situations of each adult member of the royal family was as follows: (in order of succession, therefore… sons first)

1. George, Prince Regent (and wife Princess Caroline of Brunswick) – These two are first cousins. Their one daughter was born nine months and one day following their wedding… which seems like a great beginning. However, the pair loathed each other practically upon sight (The Prince famously took one look at his new betrothed and demanded a glass of brandy.) They were living apart, completely estranged, withing three weeks of their marriage. Therefore, no further children resulted from this marriage. George had been previously married illegally to Maria Fitzherbert, a commoner, but the marriage was considered invalid, as the permission of the King had not been granted. It is believed that he had one illegitimate child with Mrs. Fitzherbert, and he may have fathered as many as five with various women.

3. William, The Duke of Clarence (and wife Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meinengen). Theirs was a companionable marriage. Adelaide was half her husband’s age, well within her childbearing years – but their two daughters died in infancy, and she suffered three miscarriages. There were no surviving children. Before he married, William lived in domestic tranquility for 20 years with his mistress, an actress named Mrs. Jordan, with whom he had 10 illegitimate children. These children (all surnamed FitzClarence), though not allowed to inherit the throne, were welcomed cheerfully to the palace after their father’s accession to the throne as William IV in 1830.

4. Edward, The Duke of Kent (and wife Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg Saalfeld). We’ve covered this one pretty thoroughly. Edward and his mistress Julie de St. Laurent (a pseudonym ) had lived together for 27 years when the call came for the Duke to marry and produce a legitimate heir. He sent his mistress away, lured more by an increase in his income than the production of a royal heir. He married the sister of Princess Charlotte’s widower – and was the oldest son to produce a legitimate child. (later Queen Victoria)

5. Ernest, The Duke of Cumberland (and wife Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz) These two are first cousins. They married for love before the death of Princess Charlotte, but their union was frowned upon by his parents, so the couple lived mostly in Germany. Upon the death of his brother King William in 1837, he became the King of Hanover, since his niece Victoria (as a woman) was disallowed from inheriting there. Ernest and his wife had a daughter that died in infancy and one legitimate son, Prince George of Cumberland (Later King George V of Hanover.) This son was third in line to the British Crown (after his father) until Queen Victoria began having children in 1840.

6. Augustus, Duke of Sussex (and wife Lady Augusta Murray) Augustus’ marriage to an earl’s daughter was declared invalid, as the King had not granted his permission. Therefore, their son and daughter (given the surname D’Este)were illegitimate and unable to inherit the British throne. After Augusta’s death, Augustus married another Earl’s daughter, Lady Cecilia Buggin, again without permission from the King. They had no children. Poor old Cecilia was unable to attend royal functions with her “husband” because of her low rank, so Queen Victoria made her a Duchess (of Inverness, not Sussex) in 1840.

7. Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (and wife Princess Augusta of Hesse-Cassel). After the death of Princess Charlotte, Adolphus was sent to Germany to find a wife for his older brother the Duke of Clarence. Princess Augusta’s father had rejected that prospect, and two months later, Adolphus married her himself! The couple had three legitimate children (a son and two daughters).

And had none of these sons ever had any legitimate offspring, the daughters:

8. Charlotte, The Princess Royal (and her husband, Duke, and later King Fredrick I of Wurttemburg). Perhaps this was not the grand marriage that Princess Charlotte (known in the family as “Royal”) was destined to make. Her father King George was infuriated that Frederick had taken the title of King. He refused ever to address his daughter as the Queen of Wuttemberg. Charlotte had one daughter who died in infancy.

9. Augusta (never married) This breathtakingly beautiful princess did receive quite a few proposals. As King George grew older, he became increasingly suspicious of potential husbands for his daughters, and was more and more unwilling to allow them to marry. Augusta was 49 years old when her brother’s heir Princess Charlotte died, so it was thought unlikely she would have been able to marry and produce an heir herself.

10. Elizabeth, Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg (and her husband Frederick VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg). Elizabeth, also quite striking in appearance, also fell victim to her parents’ unwillingness to part with their daughters. Elizabeth fled her domineering mother at the age of 48 to marry for convenience. She wanted freedom and her husband needed her money and connections. It was a quite amiable marriage; however, the union produced no children.

11. Mary, Duchess of Gloucester (and her husband Prince William Frederick, the Duke of Gloucester). These two are first cousins. As a young lady, Mary had fallen in love with a Dutch prince… but her father refused to allow her to marry until her older sisters did. Was it a ploy? Hmmm. By 1816, her father had become insane and was no longer able to object. The Duke had been encouraged to stay single as a possible consort to the heir Princess Charlotte…. but with her marriage to Prince Leopold earlier that year, he was free to marry. Both the bride and groom were over 40 when they married; they had no children. Mary was Queen Victoria’s favorite aunt.

3. Mourning jewelry

JET:

Victorian mourning dictated the strictest of plainness – beyond the wearing of head-to-toe black, the fabrics themselves were not to have any shine to them (lest they appear too cheerful).

Diamonds, obviously, would be far too happy for the occasion – and gold was simply out of the question. Queen Victoria herself dictated that no jewelry was to be worn for the first year of court mourning unless it was made of unpolished jet.

Jet, with its low sheen and inky color, was the perfect medium to demonstrate one’s sense of loss.

A jet locket, containing photos of the departed (in this case, thought to be parents and grandparents).

So what *is* jet? Simply put, it’s fossilized wood. Jet was created by time and pressure from the remains of evergreens that were last alive during the Jurassic period! “Knockoff” jet, which was quite a bit less expensive, was often made from hard coal, glass, gutta-percha, horn, or rubber (cleverly renamed as “Vulcanite.).

The town of Whitby, in northern Yorkshire, had long been a source for this material. The Romans of the third century AD used jet to make pendants (in the shape of Gorgon heads), dagger handles, small bottles, and rings of all descriptions. These items have been found all over Europe – but the excavation of an actual jet workshop in Yorkshire has led experts to believe that the area near Whitby was the source for all the finished examples.

During medieval times, jet was seen as a protection against dogs – leading to the poachers’ habit of wearing jet jewelry during their nightly prowls.! (We love this superstitious use.)

Many religious articles, including rosaries and crosses -have been made of this material, which was thought to be supremely effective in warding off the influence of evil and of witches. The pilgrims at Santiago de Compostela were sold souvenir medallions made of jet to commemmorate their long journeys.

The Victorians hauled jet back out of obscurity – it was fashionable again, even for those not in official mourning. Jet polishes quite well – perhaps the dull beads of early mourning could be “recycled” in this way for later use.

HAIRWORK:

Jewelry incorporating a lock of the loved one’s hair, especially when accompanied by a painting or photo, became a fashionable feature of second mourning. we’ll let this quote form a Godey’s Lady’s Book (1850) speak to the sentimental power of such a piece of jewelry:

“Hair is at once the most delicate and last of our materials and survives us like

love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a

lock of hair belonging to a child or friend we may almost look up to heaven

and compare notes with angelic nature, may almost say, I have a piece of thee

here, not unworthy of thy being now.”

Not only the recently bereaved wore hair as ornaments; the clever use of hair as a craft material was a fashion raging across Europe. You could view extravagant pieces of artwork and jewelry during the Grand Exposition in the Crystal Palace. It became a drawing-room sensation, with friends exchanging bracelets or rings, and clever scenes from nature re-enacted in assorted colors of hair. Lovers had been giving each other such mementoes for centuries – (remember Marianne giving Willoughby a lock of her hair in Sense and Sensibility?)

But it took the Victorians to make a fetish of such things.

WANT MORE?

Susan and I are actually within striking distance of Leila’s Hair Museum in Indepeendence: http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/11479

Here is a link to some instructions, materials, and finished examples: http://www.victorianamagazine.com/jewelry/hairjewelry.htm

And for a blog We highly recommend devoted to all types of mourning jewelry, funeral practices, and memorials – please see: http://www.artofmourning.com/

2. Victorian Mourning Practices

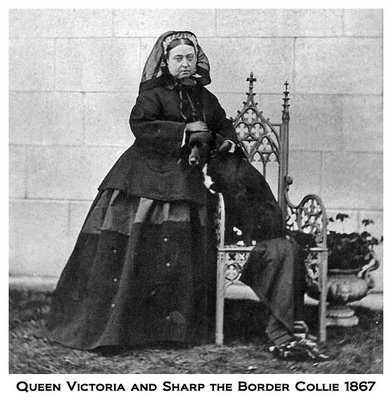

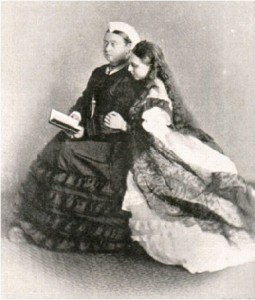

Queen Victoria mourned her beloved, Prince Albert for 40 years. She was in full mourning for three years and demanded that those around her did the same. She remained in half mourning for the rest of her life.

Because of the Queens strict standards, society followed her with middle and upper class protocols for mourning. To not follow them was considered improper and would get tongues a ‘tsking. What did this mean, exactly? Clocks were stopped at the time of death, mirrors were covered in dark fabric, sunlight was curtailed behind drawn curtains, and elaborate funerals were held.

During the post mortem viewing of the deceased, usually in the home, photography would take place and it was a very hands on experience for all in attendance. An entire industry of Victorian post mortem photography focused on portraiture of not only the deceased in repose, but also propped up and sitting among the living.

How else did well-to-do Victorian era families mourn the loss of a loved one? It played out in the wardrobes.

And we looooove to talk wardrobes!

Full mourning, which most widows kept for a year and a day following the passing of a husband, required dressing entirely in plain, black clothing- no bling. The material for these dresses was often silk crepe, because it had a very dull sheen. When the widow went to church (the only accepted outing) she would wear a black veil. After this time, if necessary, the woman could marry again.

The second phase of mourning generally lasted for approximately the next three- six months of the second year. The black dress and veil were still worn, but trim could be added to the dress, mourning jewelry could be worn, and the veil was lifted, but only to the back of the women’s heads.

Wait! Mourning Jewelry? Oh we love that too much to not devote an entire special feature to it, but basically, mourning jewelry was often made to include a lock of hair and a photograph of the deceased. Naturally, the more wealthy a family, the more elaborate not only the jewelry but the entire mourning wardrobe. Middle class families would often dye dresses black for mourning, and then bleach the black out at the end of the mourning period.

Finally, the last stage of mourning lasted about nine months was called half mourning. First more elaborate trims we added on the black dresses, then a slow easing into color- gray, white, lavender, and mauves were worn in addition to the black. Any type of jewelry could be worn at this time.

The entire process for a woman mourning the loss of her husband, unless you were an overachiever like Queen Victoria, was about two full years.

What about the rest of the family? Widowers wore somber colored suits for about the same amount of time as a widow would, however they were still expected to work and they could determine when they were ready to remarry.And, yes, Victorian male fashions were usually dark colored so really, there wasn’t much of a difference.

If children were mourning the loss of a parent, they would follow the regime for about a year, never more, and they did not have to follow the very strict practices of a woman if they had not yet come out in society.

With the passing of Queen Victoria herself, these strict protocols were eased as were many traditions and practices of the Edwardian era that followed.

1.The Children of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert:

1. “Vicky” : Victoria Adelaide Mary, Princess Royal, (born 1840); married Frederick III of Germany (8 children, including the infamous Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, Queen Sophia of Greece, and one daughter named Viktoria)

Queen Victoria considered her quick-witted, thoughtful daughter to be the child most like her in temperament. Vicky was the most prolific letter-writer of all of Queen Victoria’s children – thousands of letters between mother and daughter survive. Vicky’s own eldest son became quite aggressive, frightening, and anti-British; her son’s personality was a frequent topic of this communication. Bizarre fact: Queen Victoria had Vicky’s first baby tooth made into an odd enamelled brooch in the shape of a thistle (with the tooth as the flower.) Vicky died of cancer in 1901, age 60.

2. “Bertie” : Albert Edward, King of England as Edward VII, (born 1841); married Princess Alexandra (“Alix”) of Denmark (6 children, including King George V of England, Queen Maud of Norway, and one daughter named Victoria)

Bertie’s struggle to find his place in the world has been well documented on The History Chicks – as well as his love for American heiresses (and ladies in general.)

His birth was the first occasion in English history that a Queen Regnant had given birth to an heir. His parents placed high expectaions upon him – unfortunately, he was doomed to appear dull between his intelligent sister Vicky and his brilliant sister Alice, and suffered greatly by comparison. His parents set about molding him by a rigorous system of education that forced him to work beyond his abilities. His childhood was marred by fits of temper and loneliness. The fact that he was kept from the aristocracy’s “pernicious influences” by his parents may have been the reason he was so open to the novelty of all those American heiresses appearing on England’s shores.

Though having been compared unfavorably with his father for his entire life, Bertie proved to be a popular and responsible king during his brief nine-year reign. His last mistress, Mrs. George Keppel, (ancestress of Camilla Parker-Bowles), was brought to him in his last illness by his open-minded wife. He died in 1910 of heart failure, possibly related to his lifelong habit of smoking.

3. “Alice” : Alice Maud Mary, (born 1843); married Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse (7 children, including Alexandra, the ill-fated last Tsarina of Russia, and one daughter named Victoria)

Poor Alice did not lead a charmed life. Upon the death of her father, Princess Alice spent six stressful months as her mother’s round-the-clock secretary. Her wedding day was considered “more of a funeral than a wedding,” as the entire party wore unrelieved mourning dress during the shortened and private ceremony (though Alice was allowed to wear white for just the ceremony itself). Her married life was marred by relative poverty and an often-strained relationship with her mother, her husband, and her new country.

Alice took a great interest in nursing, and was especially impressed with the work of Florence Nightingale. She founded a hospital and a nurse’s training school, and was heavily involved in fundraising for women’s issues. Alice’s youngest son, “Frittie”, died tragically from a fall from a 20-foot high window in 1873- and Alice never recovered from her favorite child’s death. During a family outbreak of diptheria (in which her daughter Marie perished), Alice caught the disease and died at the age of 35 – on the anniversary of her father Albert’s death. Her youngest daughter, Alix, was the wife of the last Tsar of Russia, all of whose family was murdered in the Russian Revolution of 1917.

4. “Affie”: Alfred Ernest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh and of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, (born 1844); married Marie Alexandrovna, Grand Duchess, Russia (5 children, including Queen Marie of Romania, and one daughter named Victoria)

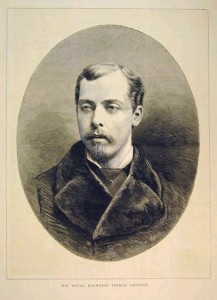

Prince Alfred was eager to join the Royal Navy – It suited his adventurous personality to a tee. Rising quickly through the ranks, he was made captain of his own ship, the Galatea, when he was only 22… and promplty set off on an around-the-world tour. During his visit to Sydney, he was shot in the back by a would-be assassin, but recovered from his injuries in a metter of weeks. He was the first British prince to visit many countries, including Australia, India, Ceylon, and India. He sounds a lot like an Indiana Jones crossed with James Bond- I bet he was quite dashing!

He became Admiral of the Fleet in 1893, at the age of 49… but shortly afterward inherited his father’s homeland, becoming the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha that same year. He reigned for seven years until his death of throat cancer in 1900, at the age of 66.

Affie on his trip around the world, in Tahiti. (Affie is in the center. The women are all of the Salmon/Brander family, who acted as royalty of the island at the time.)

5. “Lenchen”: Helena Augusta Victoria, (born 1846); married Prince Kristian of Schleswig-Holstein (5 children, none of whom had the first name Victoria)

Lenchen was the tomboy and plainest sister of the family, Feeling familial pressure building to stay unmarried and care for her increasingly demanding mother, Lenchen jumped into a companiable marriage of convenience. Her husband was 15 years her senior, and the pair enjoyed 51 years of comfortable and friendly married life. They stayed in Britain at the command of Queen Victoria.

Lenchen was one of the founding members of the Red Cross, and president of the Royal British Nurses’ Association. She was an active campaigner for women’s rights (much to the displeasure of her mother!) Princess Helena died in 1923, aged 77.

6. Louise Caroline Alberta (born 1848) ; married John Campbell, Duke of Argyll, Marquis of Lorne (no children)

Louise was widely considered to be the most beautiful of Victoria’s daughters, as well as being the non-conformist of the family. The Queen allowed her to attend art college, (so she became the first English royal princess to attend college), and was the only child to marry a commoner, Lord Lorne (later made Duke of Argyll). A royal princess had not done so since 1515, when Mary Tudor, sister of Henry VIII, married the Duke of Suffolk (born simply Mr. Charles Brandon.) Louise is the creator of the famous statue of Queen Victoria in the gardens of Kensington Palace.

Some say that Sir J. E. Boehm was, in fact, the sculptor.. but Princess Louise’s talent belies this theory.

7. Arthur William Patrick, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (born 1850); married Duchess Louise Margaret of Prussia (3 children)

Arthur was Queen Victoria’s acknowledged favorite son. He was named after the famous Duke of Wellington, and followed his namesake into a military career.Always of a military temperament, Arthur soon became a soldier and saw quite a bit of action. He was made a general of the army in 1893, having climbed gradually through the ranks during his military career. He became Governor-General of Canada in 1911, and became quite involved in the preparation of Canadian troops for their involvement in WWI. Upon his return home, he became the president of The Boy Scouts Association.

Arthur had a long-lived and well-known affair with Jennie Jerome Churchill’s younger sister Leonie, Lady Leslie – while still maintaining a good marriage with his wife. When he died aged 91 in 1942, he was (and still is) the longest lived prince of British royal blood.

8.”Leo”: Leopold George Duncan, Duke of Albany (born 1853); married Princess Helena Frederica of Waldeck (2 children, his son married a Victoria!)

Prince Leopold was born with hemophilia, which is a condition causing blood to coagulate very slowly and inefficiently. Injuries to joints or internal organs can bleed for extended periods of time. Most sufferers of hemophilia at this time period had a life expectancy of only 11 years, but Leopold had a retine of doctors near him at all times.

Leopold was unable to pursue any sort of a military career due to his delicacy, so he was made unofficial secretary to his mother, often privy to secrets which Queen Victoria withheld from her heir, Bertie. This caused enormous tension beetween the brothers.

Leopold suffered from near-debilitating joint pain, and in 1884, when he slipped and injured his knee, he was given a large dose of morphine. He died in the early hours of the next morning, aged 30, apparently from the effects of too much morphine (unconfirmed.) His son was born 4 months posthumously.

9. “Baby”: Beatrice Mary Victoria (born 1857); married Prince Henry of Battenberg (4 children, including QueenVictoria Eugenie of Spain)

Beatrice was a favorite of both of her parents from the very beginning. Prince Albert described her as “the most endearing baby we’ve had.” Queen Victoria even took special pains to spend time with her youngest child – hours many of the other children were denied. After the death of Prince Albert, the cozt family of Beatrice’s childhood was plunged into mourning. Beatrice grew up in an atmosphere of hushed words and black clothes, becoming more important to her mother with the departure of each of her other children in marriage.

Queen Victoria had determined that her last child would remain single as her constant companion, but Baby had other plans. She had fallen in love with Prince Henry of Battenburg, and declared her intention to marry him. Queen Victoria responded by refusing to speak to her daughter for SEVEN MONTHS, communicating only by note. Beatrice must have inherited the same stubbornness, becuase she won the day and was allowed to marry her prince if he consented to live with his new wife in the palace with the Queen. Beatrice’s children were the ones who put crocodiles under Queen Victoria’s desk, made forts out of the dispatch boxes, and basically ran riot over their grandmother’s dignity.

After Queen Victoria’s death, Beatrice carefully censored all of her mother’s journals, cutting out items she deemed unsuitable for public consumption, and burned the originals. (Heartbreaking for the historian – the revised journals are only 2/3 as long as the originals!) Beatrice died peacefully in her sleep in 1944, at the age of 87.