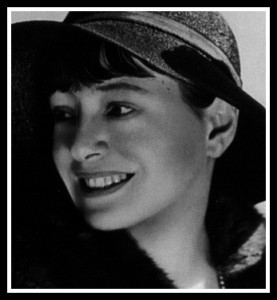

She gave us fabulous quotes like, “Men seldom make passes at girls who wear glasses” and “Brevity is the soul of lingerie,” but Dorothy Parker’s life wasn’t all wit and snark. Behind those flip one liners there was a very complex woman who lead a full life far beyond the banter of the Algonquin Round Table.

How complex was she and how full was her life? It’s going to take two episodes, that’s how much. (It’s okay, we were a little surprised, too.)

How complex was she and how full was her life? It’s going to take two episodes, that’s how much. (It’s okay, we were a little surprised, too.)

It was a dark and stormy night (what? It was!) when Dorothy Rothschild was born in West End, New Jersey at her family’s summer house on August 22, 1893. Her father Henry had fallen in love and married the girl next door, Eliza, and the pair had three children before Dorothy came along. They lived fairly affluently in New York; life as a Rothschild (not those Rothschilds) was very comfortable.

During a typical summer at the shore when Dorothy was five, Eliza suddenly died. Henry was inconsolable. He sold their house, moved the family a few times around New York City and, when he realized that he needed a wife to raise his children, he married. Eleanor- on paper- -sounded a lot like Eliza, but if your step-kids call you “Mrs. Rothschild” (or nothing at all) you can pretty much assume you are not at all like their mother.

We go into far greater detail in the podcast about things like the dirt on Jewish Dorothy’s Catholic school education, her troublemaking ways and why she thought she was responsible for the death of her stepmother (she wasn’t). We chat about the antics of short, dramatic, artsy and moody Dorothy when she was sent to Miss Dana’s School for Girls where most of the student body was anything but short, dramatic, artsy and moody.

By the age of 14 Dorothy’s formal education abruptly and mysteriously ended. She loved to read and write “verses” with her father, but as Henry was aging and her brothers and sisters moved on to adult lives, Dorothy was left to care for him. Dorothy and Henry would spend winters in New York and summers at the shore for six full years before Henry passed away.

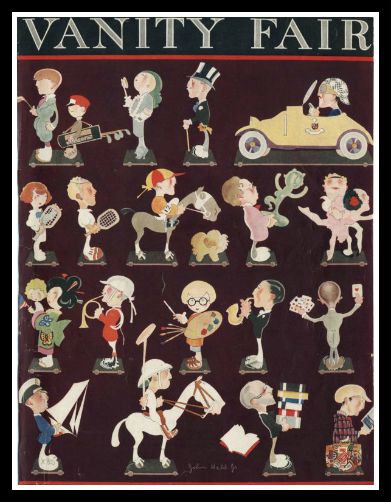

Henry’s estate wasn’t large enough for Dorothy to live on for the rest of her life, so in 1914, 21 year-old Dorothy Rothschild set off on her own. She moved into a boarding house, got a job playing piano at a dance school and spent a great deal of time writing poetry and submitting them to magazines. Empowered by the success of her first poem being accepted for publication, she put on her best suit, walked into the office of the editor of Vanity Fair magazine and asked for a full time job as a writer.

And he sent her away.

But a few months later he got in touch with her, told of a position at Vogue and Dottie dove in. So what if it was a fashion magazine and not the meatier Vanity Fair? She was a writer…(tiny font) of picture captions.

Dorothy was small, well bred and articulate with large eyes and an ingenue look (although not quite the demure personality to match). She attracted the eye of many a man and was especially drawn to Edwin Pond Parker. He was a stockbroker, play/partyboy who drank a lot and didn’t care that his old Connecticut family weren’t thrilled that their son had fallen for a Jewish girl from New York. (This worked out fine because they weren’t invited to the wedding when Dorothy and Eddie married in 1917.)

What was happening in 1917 besides the fun loving Parker’s setting up house? World War I. Eddie headed off to the military while Dorothy threw herself into her work developing her witty style that soon landed her in the offices where she knew she belonged: Vanity Fair.

Dorothy fit into the magazine of pop culture, politics, art and lifestyle of New York perfectly. She began as New York’s only female theater critic and her sophisticated, sharp, funny reviews very quickly gained a large audience while the shenanigan filled office environment fueled her. It was during this time that a simple lunch of writers and critics at a local hotel morphed into a daily event of verbal sparring and witty banter from Jazz Age New York’s literati and reporters. What was said at the table would be quoted in newspaper columns and spread throughout the country. The group called themselves the Viscous Circle but, because of their large table in the middle of the hotel dining room, they were recognized as the Algonquin Round Table.

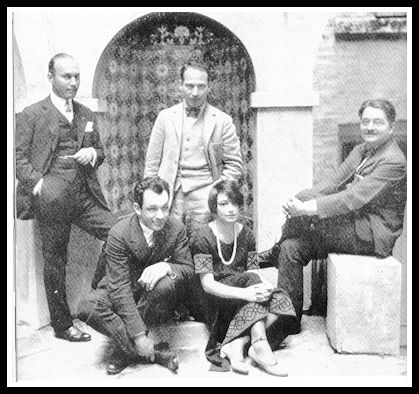

Some Round Table members: Art Samuals, Charles MacArthur, Groucho Marx, Dorothy Parker and Alexander Wollcott

When Eddie returned from the war he was addicted to both alcohol and morphine and their marriage started to skid out of control. About the same time Dorothy stepped over the line in a review and was replaced at Vanity Fair. She scrambled for more work, began to write short stories as well as any freelance writing she could. A few of her Round Table friends began a new magazine, The New Yorker, and she began writing book and theater reviews but the days of the party work atmosphere were gone.

And then Eddie was gone, too. The couple finally divorced in 1928, but that wasn’t the end of the drama in her life, not by a long shot.

Media recommendations will be on the shownotes for Part Two, so go fix yourself a little nip and when we return: Part Two of the life of Dorothy Parker.